Urban redevelopment has largely passed by the Reservoir Hill neighborhood of Baltimore. Many of its stately row houses are showing their age. The business district has been torn down. The pavement on the streets has seen better days.

There’s a beehive of activity where those businesses used to be. But it doesn’t involve activities normally associated with an urban neighborhood. That’s because the oasis in the center of the neighborhood isn’t very city-like. It’s the Whitelock Community Farm.

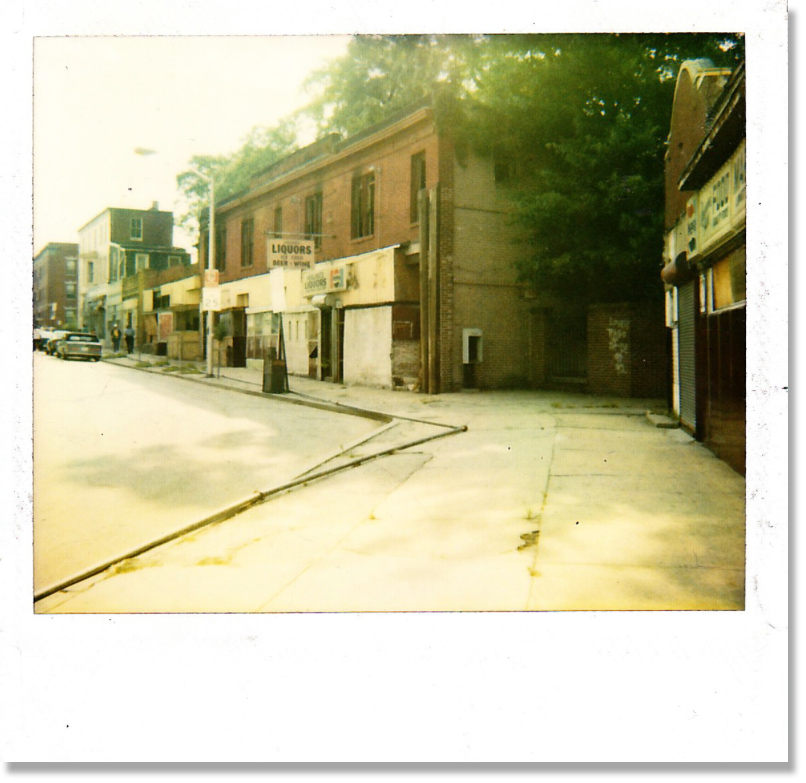

The farm is located on Whitelock street, the main east-west passage through Reservoir Hill. The prime location used to be the neighborhood’s commercial center before it was torn down in 1970s.

The Whitelock Street business district in Reservoir Hill is shown in a 1980s Polaroid photo. / Image courtesy of the Reservoir Hill Improvement District

“It was still functioning, but it was functioning in a way that’s not healthy for the neighborhood,” said Russ Moss, a Reservoir Hill resident since 1994, and a longtime member of the Reservoir Hill Improvement Council.

Baltimore holds a unique place in the history of U.S. housing segregation. Between 1860 and 1960, the Jewish community in Baltimore grew tenfold, but under restricted covenant rules, they were excluded from many suburban neighborhoods. Banks and real estate agents used “redlining” to discriminate against Jewish and African American people by refusing to back loans to them until 1968.

Moss said that when the Jewish population moved out of the neighborhood, blacks began to move in. Single family dwellings were chopped up into apartments. There was an influx of new black residents moving into Baltimore from the Deep South in search of job opportunities after World War II, but they were restricted in where they could live. Reservoir Hill was one of those places, so the area became “pretty much a slum.”

Today, the neighborhood is 93 percent black, with a median income of about $24,000. On average, the household income is $30,000, which is just above poverty line.

Carl Cleary is the housing coordinator of the Reservoir Hill Improvement Council. He said the neighborhood has been working to create more home ownership in the area. They are counting on an influx of new residents to occupy row houses that are being renovated across Reservoir Hill.

He said the presence of Whitelock farm at the center of the neighborhood is attractive to potential residents.

“I always say it’s almost an eye candy,” Cleary said.

The farm’s value lies in more than its attractiveness. “On the other side, it’s productive. They raise herbs and plants for local restaurants. They provide community service hours and placement for students. All kinds of benefits,” he said.

Image posted to Instagram was tagged with the message: "See you this Saturday for spring veggies, seedlings for your garden and we will have our smoothie bike out!"

Broken promises and a change of heart

Whitelock didn’t begin as the community center that it is today.

“When the retail stores were torn town, the neighbors were promised that new businesses would be brought back in. That didn’t happen,” Cleary said. Potential developers didn’t see enough potential profit in a black neighborhood, he said.

Nearly a full city block of land became vacant – or a “flatland,” as they’re called in Baltimore. Neighbors and volunteers banded together to keep it from becoming a weed-choked wasteland by converting the property into a community garden. Then the garden evolved into a farm.

Not everyone bought into the idea of an urban farm, especially when they didn’t see how they could benefit from it. Some argued that the hoop houses built with plastic and wires were an “eyesore” in this historic neighborhood, where beautiful Victorian architecture is the norm.

“With what people weren’t expecting to see, there came some natural resistance,” Cleary said.

Farm manager, Alison Worman, and programs manager, Isabel Antreasian, both said they believe they’ve earned the neighborhood’s faith by being consistent.

“Every summer we have our farm stand open on Saturdays,” Antreasian said, “That means every Saturday, one after another. Rain or shine.”

Running a farm is a lot of work. Other than working on the farm’s production, the duo spends much of their time recruiting volunteers, managing youth work programs, maintaining their partnership with multiple local restaurants and markets, applying for funding and, last but not least, being there for the community.

Louies Hayes is a longtime Reservoir Hill resident and the property manager of a residential building a block away from Whitelock Farm.

Hayes said he remembered the first time he went to get produce from the farm. He took a picture of his three-year-old son holding a carrot in his hands.

“He had never seen it before,” Hayes said.

Hayes said it is good to be able to buy fresh vegetables and fruits grown inside the neighborhood at a corner store in the neighborhood. That’s a perk for a neighborhood that doesn’t have a nearby supermarket.

Worman, the farm manager, said Whitelock would continue to serve the community as long as it is needed.

She said it has been wonderful to see the neighborhood take up ownership of the farm.

“We are required to hold a community meeting in order to get our lease from the city renewed,” Worman said. “And without prompting, the neighbors touched down on the benefits of having the farm.”

Despite the neighborhood support, Whitelock’s future is not assured. The biggest threat comes from below.

Under West Baltimore runs one of Amtrak’s aging railroad tunnels, which is considered a major bottleneck in a transportation network designed to take goods from the city’s seaport to inland destinations. The chokepoint is the dimension of the existing tunnel, which is too small for modern shipping containers to pass through.

In 2015, Amtrak, the Maryland Department of Transportation and the Baltimore City Department of Transportation proposed relocating the B & P tunnel.

The proposal to rebuild the tunnels would allow more trains, with larger payloads to pass through the busy corridor more quickly each day. It would boost Baltimore’s economy greatly.

The tunnel for the $4 billion project passes directly below Reservoir Hill. On paper, there is one piece of property not covered by dwellings. To the developers, it looks like the perfect location for an air vent. To the neighborhood, it looks like the center of “their” Whitelock farm.

The plan calls for a five-story plant to ventilate the tunnel above surrounding buildings.

Swapping their green oasis for a ventilation plant is meeting fierce opposition from the neighborhood.

Reservoir Hill residents are also concerned about how vibration from trains below them will affect their century-old brick homes. To add insult to injury, the densely-populated neighborhood would lose dozens of parking spaces.

The neighborhood’s response is the formation of Residents Against The Tunnel (RATT). Moss has been one of the strongest voices in opposing the rebuild.

“I hope it stays a green space,” Moss said. “I think it’s crucial to the neighborhood becoming livable.”

RATT’s opposition seems to be paying off. In April, the governmental agencies and private developers revised their plan to relocate the air vent away from Whitelock farm.

It takes village to own a farm.