Media Effects Research Lab - Research Archive

The effects of emotion on creativity

Student Researcher(s)

Elizabeth Hutton (Ph.D Candidate);

Faculty Supervisor

FOR A COMPLETE REPORT OF THIS RESEARCH, SEE:

Elizabeth Hutton & S. Shyam Sundar (2008, May). Can Video Games Enhance Creativity? An experimental investigation of emotion generated by Dance Dance Revolution. Paper to be presented to the Game Studies Division of the International Communication Association at the 58th annual conference in Montreal, Canada.

INTRODUCTION

Educational technology, particularly video games, has captured the imagination of students and has been associated with emotion. Curiosity, fantasy, and challenge are essential characteristics of computer games with educational uses that are intrinsically enjoyable or fun (Malone, 1980). It is well known that teachers use emotion in the classroom to encourage students to learn, and there is some evidence that emotional arousal enhances cognitive functioning (Isen, 1987). But much of the research on the effects of emotion on cognition has had mixed results, especially its effect on creativity. How does emotion enhance or diminish creativity? Does the valence or arousal (i.e., the intensity of emotion) improve creative thought?

RESEARCH QUESTIONS & HYPOTHESES

RQ1: How do various facets of creativity vary as a function of emotion, defined for this experiment as valence and levels of arousal, either independently or together?

RQ2: How do energy levels either physical or mental vary as a function of levels of arousal?

Hypotheses:

H1: Lower arousal levels will be associated with higher creative scores.

H2: As the level of arousal induced by exercise increases, self-reports of energy levels during a subsequent creative task will increase, up to a point.

H3: High and low levels of arousal will result in lower creativity.

H4: Positive valence will have a significant effect on ideation, while negative valence and arousal will have none.

H5: A positive mood will increase the number of original ideas produced.

H6: A positive mood will facilitate fluency.

H7: A positive mood will result in higher creative self-efficacy scores.

METHOD

To examine the direct and combined effects of arousal and valence on creativity, a 2 (mood) x 3 (physical exertion) between subjects factorial experiment was conducted. The first independent variable was valence with two conditions, either a positive or negative mood, and the second independent variable was arousal with three levels of physical exertion, low, medium, and high. The valence of mood was induced by manipulation of a score on a purposefully ambiguous emotion recognition test, while the level of exertion was based on playing the video game Dance Dance Revolution at three levels of exertion: low, medium and high.

There was one dependent variable: a creativity test, the Abbreviated Torrance Test for Adults (Goff & Torrance, 2002) to measure divergent thinking. Divergent thinking, an aspect of creativity, is the tendency to respond to problems with a diversity of ideas (Toplyn, 1999).

PARTICIPANTS

A total of ninety-eight participants initially took part in the study. Ninety-seven were undergraduate and graduate students enrolled at a large university in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States, and one was a prospective student. Eighty participants received class credit; eighteen participated without any credit in order to observe how a quantitative research study is conducted. All students who received extra credit had an opportunity to receive the same amount of credit by completing an alternative assignment.

The researcher recruited students face-to-face from communication and education classes and explained that the purpose of the study was to explore the relationship between emotion and cognition, through the video game Dance Dance Revolution. Students interested in participating signed up during class for a date and time to come to a media effects lab on campus. All participants signed an informed consent form prior to their participation in the experiment.

RESULTS

A 2 (mood) by 3 (level of exertion) factorial ANOVA was conducted to test the effects of arousal and valence independently and together on creativity. The analysis yielded two effects for arousal: one near significant effect on flexibility, a subset of creativity, and one main effect on self-reported attentional intensity. A main effect for valence on originality, a subset of creativity, approached significance. In addition, there were two significant interactions between arousal and valence, one for the creativity index, and one for a subset of that index, fluency.

Hypothesis 1 predicted that lower arousal levels would be associated with higher creative scores, while Hypothesis 3 predicted the opposite: high and low levels of arousal would result in lower creativity. A factorial ANOVA revealed that a main effect for level of exertion on flexibility approached significance F(2,84) = 2.71, p = .07; See Figure 1). A significant quadratic trend = 3.1, p < .05 lends support to Hypothesis 1, but not to Hypothesis 3. The near significant effect of arousal on flexibility indicates that a low and high level of arousal, rather than a medium level, is more likely to improve the ability to process information or objects in different ways.

Figure 1: Flexibility as a Function of Level of Exertion

Hypothesis 2 predicted that an increased level of arousal induced by exercise would result in a report of increased energy, but only up to an optimal level. A factorial ANOVA revealed a main effect for level of exertion on post-stimulation attentional intensity (F(2,81) = 3.38, p < 0.05), with participants at a medium level of exertion reporting a significantly higher mean score for attentional intensity (M = 30.57) than those who participated at a high level (M = 26.77) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Attentional Intensity as a Function of Level of Exertion

Hypothesis 4 predicted that positive valence would have a significant effect on the generation of ideas, whereas negative valence and arousal would have none. Hypotheses 5 and 6 respectively, predicted that a positive mood would increase the number of original ideas produced, and a positive mood would increase the number of ideas. There was no main effect for valence on the creativity index score (F (1,84) = .14, p > .05). A factorial ANOVA revealed a near significant main effect for valence on the number of new ideas (originality) F (1,84) = 3.20, p = .08, but in the opposite direction predicted by Hypothesis 5 (see Figure 3). A negative mood produced more original ideas than a positive mood. There was no main effect for valence on the number of ideas produced (F (1,84) = .55, p > .05).

Figure 3: Originality as a Function of Valence

Hypothesis 7 predicted that a positive mood would result in higher creative self-efficacy scores. There was no main effect for valence on creative self-efficacy (F (1,83) = .00, p > .05).Although not hypothesized, the following findings lend support to the overall idea of this study that emotion does significantly affect creativity. A factorial ANOVA revealed two significant interactions between valence and arousal: one on the overall creativity index (F (2,84) = 3.43, p < .05)(see Figure 4) and one on fluency or number of ideas (F (2,84) = 6.65, p < .01)(see Figure 5).

Figure 4: Creativity Index as a Function of the Interaction Between Valence and Arousal

Figure 5: Fluency or number of ideas as a Function of the Interaction Between Valence and Arousal

While Hypothesis 1 was supported in that lower arousal levels were associated with higher creative scores, the interaction extends that finding and shows a more complex picture of the effects of emotion on creativity: low exertion (arousal) levels resulted in higher creative scores only when coupled with a negative mood. At high exertion levels, a positive mood resulted in higher creative scores. The significant interaction between valence and arousal on the creative index lent no support to the prediction of Hypothesis 3 that high and low levels of arousal will result in lower creativity.

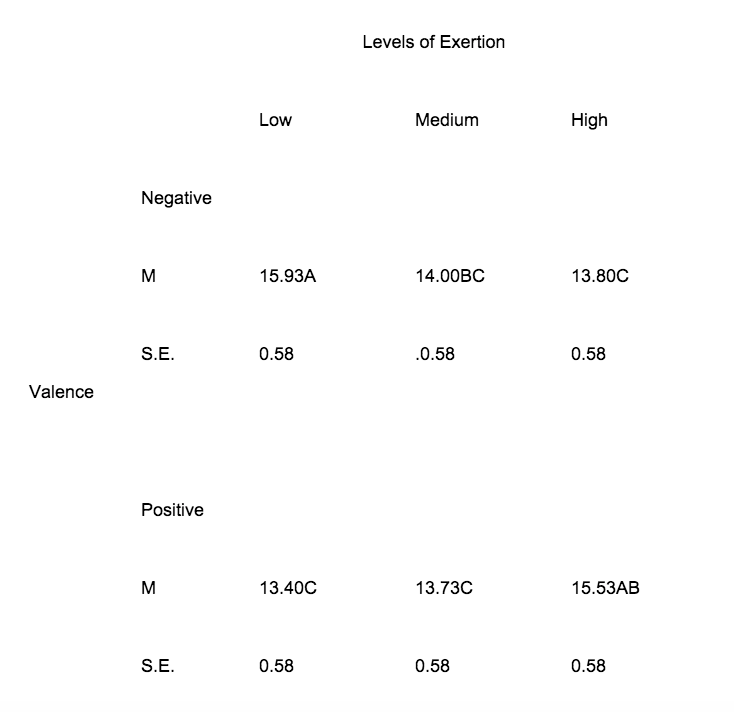

While Hypothesis 4 predicted that positive valence would have a significant effect on the generation of ideas, the interaction provides support for that prediction only at a high level of exertion. Contrary to the prediction of the second half of Hypothesis 4, that negative valence and arousal would have no effect on creativity, the interaction shows that when combined, negative valence and a low level of exertion yield the highest creativity index scores. Table 1 shows the means associated with this interaction, and illustrates that a negative valence-low exertion level condition was significantly higher than either a negative valence-medium exertion level or a positive valence-medium exertion level. A positive valence-high exertion level was significantly higher than a positive valence-medium exertion level.

Table 1: Creativity Index Scores: Valence X Level of Exertion

Direction of valence and arousal revealed a more complex picture of emotion’s effect on fluency, similar to its effect on the overall creativity index, only stronger. Fluency is not affected by positive valence alone, but is at its highest when positive valence is combined with a high level of exertion; still, this condition was second to the highest score for fluency which resulted from the low arousal-negative valence condition. Table 2 shows the means associated with this interaction, and illustrates that a negative valence-low exertion level condition was significantly higher than four of six other conditions: a negative valence-medium exertion level, a positive valence-medium exertion level, a negative valence-high exertion level, and a positive valence-low exertion level. A positive valence-high exertion level was significantly higher than three of six other conditions: a negative valence-high exertion level, a positive valence-medium exertion level and a positive valence-low level of exertion.

Table 2 Fluency Scores: Valence X Level of Exertion

CONCLUSIONS

The Combined Effect of Arousal and Valence on Creativity

A significant interaction between valence and arousal, on the overall creativity index lends support to the main hypothesis of this study that emotion does significantly affect creativity. The idea that creativity is a complex construct with a variety of aspects is supported by strong findings for the combined effect of valence and arousal on fluency, or number of ideas; different aspects of creativity may respond to mood in unique ways, as fluency did in this study. The picture is complex and incomplete without further research.

In both of the above interactions, mood moderated the effect of arousal such that for high and low levels of arousal, valence moderated the effect on creativity. Positive valence lead to significantly greater creativity, compared to negative valence, at high levels of exertion, while negative valence lead to significantly greater creativity at low levels of arousal. At moderate levels of arousal, valence had no significant effect.

The two significant interactions of valence and arousal on the creativity index and fluency may be explained by going back to detailed accounts of Yerkes-Dodson experiment. Yerkes and Dodson (1908) found that “the effects of the shock [to the mice] were more pronounced in difficult discriminations and the optimum level of shock was higher in easy discriminations” (Kahneman, 1973, p.34).

If one thinks of an unexpected negative mood manipulation as the equivalent of a shock, then at the higher levels of arousal, a negative mood manipulation might cause creative performance (the equivalent of difficult discriminations) to drop, whereas at lower levels of arousal it might cause performance to rise. Perhaps this aspect of Yerkes and Dodson’s experiment explains why the combination of low arousal-negative mood resulted in high creative scores, and the combination of high arousal-negative mood resulted in lower scores.

The Effect of Arousal on Creativity

The finding that self-reports of mental energy (attentional intensitiy) rose in association with the change from low to medium levels in exertion, and then decreased, at the high level of exertion, follows the pattern set by Yerkes-Dodson law where arousal has an optimal level beyond which performance decreases. If as hypothesized, creativity is associated with broad and diffused attention, then a high attention level would focus on central and highly relevant cues, not incidental and remote cues. Those cues become available only at low and high levels of exertion when attention become broader and defocused, resulting in an increased pool of resources from which to draw creative thoughts. In this study, arousal at a low and high level, had a near significant effect on flexibility, the ability to process information or objects in different ways, indicating support for this line of reasoning. Together the findings support the associational theory of creativity and supports the importance of the intensity of arousal in deploying attention either in a narrow or a broad way in order to retrieve resources used in the construction of creative thoughts. They imply that intensity or arousal does enhance capacity as suggested by the activation theory of arousal.

The Effect of Valence on Creativity

The effect of valence on creativity in this study was mixed. A main effect for negative valence on originality approached significance, a finding that was not predicted by either affect as prime or affect as information theory. Yet when arousal is high or low, valence mediates creative output significantly, suggesting that it plays an important role, but one that is secondary to that of arousal. This secondary role may explain why blood-and-guts media is so popular despite the off-putting death and destruction on screen; viewers are drawn in by the intensity of the arousal, rather than by the positive or negative valence of the scenes.

Theoretical and Practical Implications

Is it arousal or is it valence that may improve creativity? The unexpected effect of interactions between valence and arousal on a creative index and on fluency supported a proposed link between the Yerkes-Dodson law and the associational theory of creativity (Toplyn, 1999), including the hypothesis that diffused attention seems to be associated with creativity.

The pattern of Yerkes-Dodson’s law emerged in self-reports of increased mental energy during the creativity test, that corresponded to increased level of exertion, but only up to the moderate level. This finding supports Zillmann's excitation transfer theory, discrepancy arousal theory, and the activation theory of arousal.

Given the idea that the complexity of open-ended creative tests of divergent thinking increase as a function of an individual's originality (Toplyn, 1999) , the findings of this study that those in low arousal-negative mood and those in high arousal-positive mood performed best on the creativity test, suggests that arousal will play a different role in creativity for those who bring high or average levels of originality to the process. The findings of this study support the idea from Toplyn (1999) that for those high in originality, low arousal conditions are best, whereas for those who are average in originality, moderate arousal may allow one's attention to be deployed in a way that will facilitate creativity. In any case it is the impact of the interaction of arousal and valence on attention that allows individuals to maximize limited capacity and produce new ideas (Toplyn, 1999). This line of reasoning draws from Mednick's (1962) associational theory of creativity, where diffused attention is associated with creativity, and Kahneman's limited capacity of attention ideas (1973).

For more details regarding the study contact

Dr. S. Shyam Sundar by e-mail at sss12@psu.edu or by telephone at (814) 865-2173